BY MELISSA SERENDA

For the second time, I purchased a pair of cannas to grace the large pots outside my front door. I’ve long admired these burly, big-leaved tropicals — the more so because they are close relatives to my beloved calatheas. My first attempt to grow them was from rhizomes purchased online; they grew beautifully, but were not at all the variety I had ordered. I half-heartedly attempted to overwinter them, but was neither surprised nor disappointed that they failed to make a repeat appearance the following summer. (Alas, Linda Schreiber’s article on canna storage had not yet been published at the time!)

Image via Wikimedia Commons

This year, the new cannas were an impulse buy, to fill the empty pots before a visit from relatives. From the few varieties available, I selected a small pot labeled “Canna Lily Cannova® Mango,” with vibrant pinky-orange blooms against big, pale green foliage. I chose specimens with inflorescences that were well developed, and was rewarded with the first flowers bursting open overnight within just a few days.

I’m not going to talk about growing cannas successfully, as I have yet to do so (and there are others far more qualified), but the flowers mystified and fascinated me to the point that I had to discover their secrets.

When you think of a typical flower and its reproductive parts, you probably imagine something similar to a tulip: a well-developed central pistil, with a sticky stigma at the top to capture pollen, surrounded by several pollen-bearing stamens on slender filaments.

think.

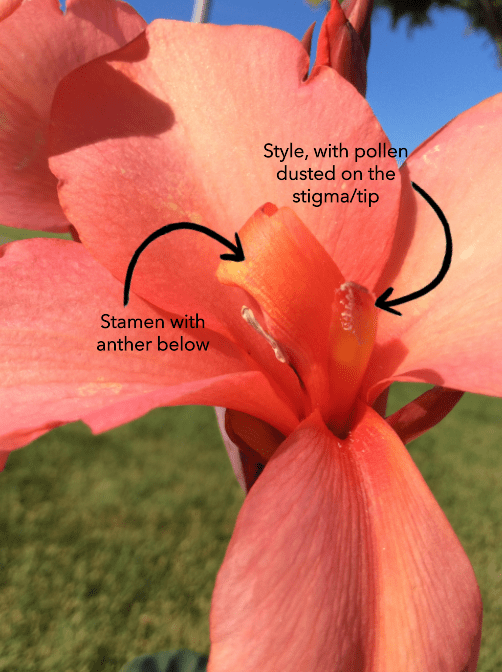

When I looked at the canna flowers, I saw no obvious pistil, no powdery anthers shedding pollen. I saw what seemed to be an assortment of pink petals: four big floppy ones (three ascending above and one descending below), one slightly smaller petal curling away from the center with kind of a hardened edge on the bottom, and a narrow, thicker petal protruding from the center like a little tongue. What is going on here?

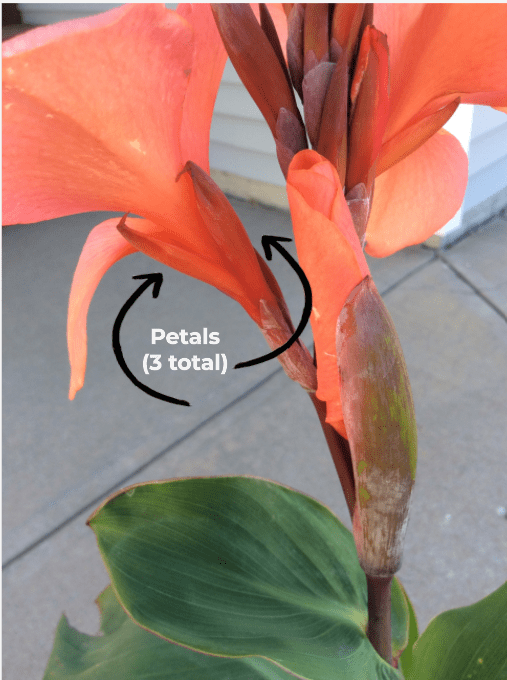

Well, to begin with … none of those are petals! The petals are actually behind the showy bits, playacting as sepals (which are even more subtle, below the petals).

What we are seeing as petals are actually the flower’s reproductive parts: the stamens and pistil! Or more accurately, several staminodes, which are structurally stamens but don’t produce pollen, plus a single pollen-bearing stamen and the pistil.

pistil and stamen, surrounded by four

petal-like staminodes.

The four big “petals” are the staminodes, with the descending one called the labellum, or lip, and acting as a landing pad for pollinating visitors. The “curling” petal with the hardened edge is actually the functional stamen: that edge is the anther that produces pollen. And the “tongue” is the pistil, a flattened style with the pollen-collecting stigma at the very tip of the underside. (I was able to brush off a bit of powdery pollen that was collected there.) It seems that the pollen can be shed from the anther onto the style before the bud even opens; pollinators, including bees and hummingbirds, brush against the style and pick up pollen as they seek the nectar at the base of the structure, carrying it to the next plant. The flower may also self-pollinate as it opens.

There’s no end to the diversity and fascination that can be found in the natural world when we stop to take a closer look!